… or at the very least, how pop science works!

A lot of people believe some version of the ‘chemical soup’ story. I wrote an essay about it a few years ago: The Chemical Self and the Social Self.

… or at the very least, how pop science works!

A lot of people believe some version of the ‘chemical soup’ story. I wrote an essay about it a few years ago: The Chemical Self and the Social Self.

My latest 3QD essay is about the mystery of human memory, and why it is not at all like computer memory. I discuss the quirks of human memory formation and recall, and the concept of “content-addressable memory”.

3quarksdaily: Why human memory is not a bit like a computer’s

Here is an excerpt:

It turns out that one of the 2017 Nobel Laureates is quite a character!

“Jeffrey Hall, a retired professor at Brandeis University, shared the 2017 Nobel Prize in medicine for discoveries elucidating how our internal body clock works. He was honored along with Michael Young and his close collaborator Michael Roshbash. Hall said in an interview from his home in rural Maine that he collaborated with Roshbash because they shared common interests in “sports, rock and roll, beautiful substances and stuff.”

“About half of Hall’s professional career, starting in the 1980s, was spent trying to unravel the mysteries of the biological clock. When he left science some 10 years ago, he was not in such a jolly mood. In a lengthy 2008 interview with the journal Current Biology, he brought up some serious issues with how research funding is allocated and how biases creep into scientific publications.”

I highly recommend watching this video, where he comes up with the term “authentic bio-gibberish” to describe the overly technical jargon used by scientists.

I was asked the following question on Quora:

Why is planning & decision making situated in the frontal lobe?

Here’s my answer:

My latest 3QD essay explores the “mind as machine” metaphor, and metaphors in general.

Putting the “cog” in “cognitive”: on the “mind as machine” metaphor

Here’s an excerpt:

People who study the mind and brain often confront the limits of metaphor. In the essay ‘Brain Metaphor and Brain Theory‘, the vision scientist John Daugman draws our attention to the fact that thinkers throughout history have used the latest material technology as a model for the mind and body. In the Katha Upanishad (which Daugman doesn’t mention), the body is a chariot and the mind is the reins. For the pre-Socratic Greeks, hydraulic metaphors for the psyche were popular: imbalances in the four humors produced particular moods and dispositions. By the 18th and 19th centuries, mechanical metaphors predominated in western thinking: the mind worked like clockwork. The machine metaphor has remained with us in some form or the other since the industrial revolution: for many contemporary scientists and philosophers, the only debate seems to be about what sort of machine the mind really is. Is it an electrical circuit? A cybernetic feedback device? A computing machine that manipulates abstract symbols? Some thinkers so convinced that the mind is a computer that they invite us to abandon the notion that the idea is a metaphor. Daugman quotes the cogntive scientist Zenon Pylyshyn, who claimed that “there is no reason why computation ought to be treated merely as a metaphor for cognition, as opposed to the literal nature of cognition”.

Daugman reacts to this Whiggish attitude with a confession of incredulity that many of us can relate to: “who among us finds any recognizable strand of their personhood or of their experience of others and of the world and its passions, to be significantly illuminated by, or distilled in, the metaphor of computation?.” He concludes his essay with the suggestion that “[w]e should remember than the enthusiastically embraced metaphors of each “new era” can become, like their predecessors, as much the prisonhouse of thought as they at first appeared to represent its liberation.”

Read the rest at 3 Quarks Daily:

Putting the “cog” in “cognitive”: on the “mind as machine” metaphor

I was asked a question on Quora about a recent study that talked about high-dimensional ‘structures’ in the brain. It has been receiving an inordinate amount of hype, partly as a result of the journal’s own blog. Their headline reads:

‘Blue Brain Team Discovers a Multi-Dimensional Universe in Brain Networks’

As if the reference to a ‘universe’ weren’t bad enough, the last author, Henry Markram, says the following:

Years ago I asked what I thought might be a naive question, perhaps on Quora: how do we really know that every cell has the same genome? Was a random sampling of the body conducted? The impression I got was that such a sampling was not conducted, or at least not done regularly and systematically. The main argument for genetic identity was theoretical: the cell division process was well understood (apparently), and the error-correction mechanisms were robust. I was always suspicious of this way of thinking. As Yogi Berra said,

“In theory there is no difference between theory and practice. In practice there is.”

Since then I’ve tried to dive into the nitty-gritty of genetics, and the level of complexity is so staggering that the confidence of theoreticians seemed misplaced. (I wrote a 4 part series on biological information for 3QD, and explored the history of genetics in the process.)

So this article in Scientific American makes a lot of sense to me. Here are some excerpts:

“Accepted dogma holds that—although every cell in the body contains its own DNA—the genetic instructions in each cell nucleus are identical. But new research has now proved this assumption wrong. There are actually several sources of spontaneous mutation in somatic (nonsex) cells, resulting in every individual containing a multitude of genomes—a situation researchers term somatic mosaicism. “The idea is something that 10 years ago would have been science fiction,” says biochemist James Eberwine of the University of Pennsylvania. “We were taught that every cell has the same DNA, but that’s not true.” There are reasons to think somatic mosaicism may be particularly important in the brain, not least because neural genes are very active.”

“Mature neurons stop dividing and are among the longest-living cells in the body, so mutations will stick around in the brain. “In the skin or gut, cells turn over in a month or week so somatic mutations aren’t likely to hang around unless they form cancer,” McConnell says. “These mutations are going to be in your brain forever.” This could alter neural circuits, thereby contributing to the risk of developing neuropsychiatric disorders. ”

“The fact specific genes only explain a small proportion of cases may be because researchers have only been looking in the germ line (sex cells), McConnell says. “Maybe the person doesn’t have the mutation in their germ line, but some percentage of their neurons have it.” Somatic mosaicism may also contribute to neural diversity in general. “It might explain why everybody’s different—it’s not all about the environment or genome. There’s something else,” says neuroscientist Alysson Muotri of the University of California, San Diego, who is not part of the consortium. “As we understand more about somatic mosaicism, I think the contribution to individuality as well as the spectrum [of symptoms] you find in, for example, autism, will become clear.””

Scientists Surprised to Find No Two Neurons Are Genetically Alike

Here is an excerpt from my latest 3QD essay:

“To attempt an understanding of understanding, I think it might make sense to situate our verbal forms of knowledge-generation in the wider world of knowing: a world that includes the forms that we share with animals and even plants. To this end, I’ve come up with a taxonomy of understanding, which, for reasons that should become apparent eventually, I will organize in a ring. At the very outset I must stress that in humans these ways of knowing are very rarely employed in isolation. Moreover, they are not fixed faculties: they influence each other and gradually modify each other. Finally, I must stress that this ‘systematization’ is a work in progress. With these caveats in mind, I’d like to treat each of the ways of knowing in order, starting at the bottom and working my way around in a clockwise direction.”

Read the rest at 3 Quarks Daily: Ways of Knowing

(I’ve collected links to all my 3QD essays here.)

I came across a nice little presentation on certain problematic ways of thinking:

Let’s Wave Goodbye to the Unconscious Mind

Here’s are two excerpts:

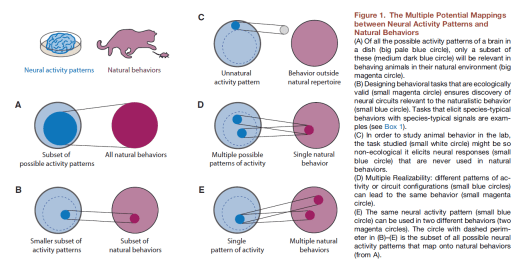

A Quora conversation led me to recent paper in Neuron that highlights a very important problem with a lot of neuroscience research: there is insufficient attention paid to the careful analysis of behavior. The paper is not quite a call to return to behaviorism, but it is an invitation to consider that the pendulum has swing too far in the opposite direction, towards ‘blind’ searches for neural correlates. The paper is a wonderful big picture critique, so I’d like to just share some excerpts.